Bound to the House, Bound to the Mountains

The snow has been relentless in the last few weeks and I have spent more time in one place that I have for years. I finally unpacked my bulky vintage cosmetics case that I lived out of for two years and at first it was a momentous occasion that seemed to signify that I was laying roots, but the more I find myself in residential West Virginia without a destination for an afternoon of gallivanting or burning calories in the sun, the more I realize that I must face the realities of my own geography and its imprint on my way of thinking. And how there are many binds here.

The idea that I received a DNA test as a gift (as many people have) is interesting to me because it turned into more than just a fun way to find out if the rumors that you are Native American are true (my rumors are not substantiated, by the way. Got Dang Mitochondrial DNA!). Ancestry found that I had a first cousin that I did not know in their database. It didn't seem completely out of the ordinary that the bastard child of a married man would have some mysteries, but it is never that easy. The record was connected to a woman that was my third cousin (this person's daughter). After a brief conversation with her, I found that there are secrets upon secrets. And whispers upon whispers - and that the illegitimate bears the illegitimate. After I found out a few things about the situation, she stopped returning my emails (I can only speculate about why). I thought that I might be more upset about that, but there is such a sense of knowing about these people that any correspondence with a secret third cousin from the bowels of Kentucky isn't going to resonate with me any more than any other random photo of a dirty-faced Appalachian family. That her eyes are my eyes are their eyes.

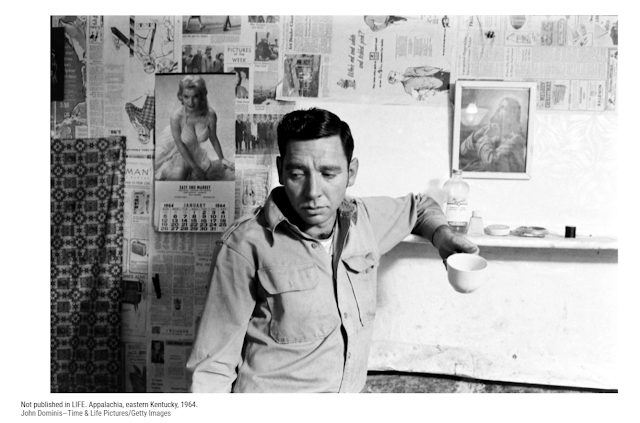

I read an interesting fact about Lyndon Johnson's singling out the Appalachian family during his Presidency to talk about combating poverty. Often seen as a way to ignore the plight of people of color during the sixties (sound familiar?), Johnson looked at this predominantly white area and declared a, "War on Poverty." Long after Johnson's, "Poverty Tour," in 1964, the reverberation of chronic poverty reaches beyond just people having money or not. Now there is a sense that Appalachian poverty (then and now) is far from access to cash. That the poverty of not-knowing how, when or why to do things to make situations better...to make people better - far surpasses the need for a steady flow of cash. That the overtones of the entire region and the children that it bore seem to be,

"It has always been this way, Jessica. You must understand that. Why are you making it such a big deal?"

Explaining Appalachia to itself and its children is as difficult as defending it to your upper-middle-class and out-of-town friends. Understanding that there is much more complexity to poverty (and lack of education and drug crises) than laziness and lack of ingenuity means that while I try to save the anger from those that marginalize, I must also save the anger from those that perpetuate the stereotype. And to do it, I must pretend like it doesn't affect me and my own successes because I am, "too smart," to allow myself to make those same excuses.

Last week, I was twelve hours away from overdrawing my bank account. I paid a utility bill too quickly instead of waiting to get paid again and in that moment I panicked because what was I going to do about it? Then I remembered a savings account. It doesn't have a lot in it, but enough to cover a winter-sized electricity bill without being completely empty. It may have taken a bit of shuffling but what would put many under water for a week didn't cause complete pandemonium. When I sat back and thought about the shuffle I cried about it. I cried because although I work diligently to make sure that I can cover for my own miscalculations - that the first place that my mind goes is to the fear and anger of this being my life. That the safety never occurs to me first. That is the poverty of being the daughter of Appalachia. I should say, this is my own personal poverty based upon what I saw and see in the world that I live in, I guess. How can I convey this to my friends and coworkers that see a map full of blue dots of poverty as a problem of personal weakness rather than a starting point for real compassionate dialogue about what it means to have less?

When I get like this - it manifests itself into understanding the reasons why I may feel chronically without. The money that I've spent to get an education that I didn't realize I was spending. That the value proposition of student loans made so much more sense when I was eighteen and thought that I would make enough to pay them back in five years while still being able to have a decent life. The money that I spent to be married and the money that I spent to be unmarried (and the money that I spent in crisis between those two points). These things have turned into confrontations have lead to meager payoffs - including one just this past December (the weekend of my birthday, no less). As if there is a dollar amount on closure or a magical payment that would lead to unending forgiveness for acts that lead to a lifetime of emotional debt. That is poverty too, though, isn't it? The idea that throwing money or credit at a problem would end the wrongness or replace people living a better life and being better to each other or better to themselves. When I bring these things up outside of the confines of therapy I seem whiny or unrealistic. That everyone feels the way that I do and understands the implications of generational poverty. They don't and I don't to the extent of those that have less than I.

"It has always been this way, Jessica. You must understand that. Why are you making it such a big deal?"

With more than one member of my family, I have spoken about how the behaviors that we dealt with in our youth will end with us because we have the opportunities and the knowledge to do better with what we have - but will they? Will we rise above the mountains? Will there ever be a point where when I miscalculate that I don't instantly lash out at the notion that no matter how hard I work or use the tools that I have that I will be without? Will all of "our generation," of impoverished hillbillies with money and credit stop partaking in risky behaviors because we start to really feel safe at our core? Will we all stop self-soothing with short-term solutions to long-term heartaches? I can't imagine that life.

Last month I went to career counseling and after a rocky start full of administrative cock-ups and disappointing scheduling snafus the counselor turns to me, looks over her glasses and says, "Well, what do you like to do?" I turned to her with all of the politeness I could muster in that moment. I gathered every good habit that I had taught myself in the years that I had become my own champion and I said very calmly, "I'm not sure who comes to do you for career counseling, but if I had the luxury to do what I liked I wouldn't need career counseling. I do what I must in order to make my life work." That is the moment when the depths of poverty are at their grandest - not when I overdraw my bank account or when I see the balance of my 401K. It may seem like a first-world idea (and I am well aware of my privilege here - but it doesn't make the pain any less real in the moments where I cannot overcome these thoughts), but the idea that we continue in our lives putting band-aids on generational poverty is what leads to my own feelings of being bound to the mountains. I look in the mirror and think that I am not capable of living up to the conversations that I have with my family about our living being different than those of our parents. That instead of hating my job at the mill or the mine - I'll hate my job in the cubicle and count the days to retirement.

It seems so hopeless, but there is a lesson: Mountains are neutral. People are poverty.

What happens next is this: If I cannot escape the mountains...I will learn them. So, when I am free of the copious amounts of snow that keep me shoveling and shoveling, I'll hit the road and go into the mountains as far as I can go when I can. And we'll see what happens.

The idea that I received a DNA test as a gift (as many people have) is interesting to me because it turned into more than just a fun way to find out if the rumors that you are Native American are true (my rumors are not substantiated, by the way. Got Dang Mitochondrial DNA!). Ancestry found that I had a first cousin that I did not know in their database. It didn't seem completely out of the ordinary that the bastard child of a married man would have some mysteries, but it is never that easy. The record was connected to a woman that was my third cousin (this person's daughter). After a brief conversation with her, I found that there are secrets upon secrets. And whispers upon whispers - and that the illegitimate bears the illegitimate. After I found out a few things about the situation, she stopped returning my emails (I can only speculate about why). I thought that I might be more upset about that, but there is such a sense of knowing about these people that any correspondence with a secret third cousin from the bowels of Kentucky isn't going to resonate with me any more than any other random photo of a dirty-faced Appalachian family. That her eyes are my eyes are their eyes.

I read an interesting fact about Lyndon Johnson's singling out the Appalachian family during his Presidency to talk about combating poverty. Often seen as a way to ignore the plight of people of color during the sixties (sound familiar?), Johnson looked at this predominantly white area and declared a, "War on Poverty." Long after Johnson's, "Poverty Tour," in 1964, the reverberation of chronic poverty reaches beyond just people having money or not. Now there is a sense that Appalachian poverty (then and now) is far from access to cash. That the poverty of not-knowing how, when or why to do things to make situations better...to make people better - far surpasses the need for a steady flow of cash. That the overtones of the entire region and the children that it bore seem to be,

"It has always been this way, Jessica. You must understand that. Why are you making it such a big deal?"

Explaining Appalachia to itself and its children is as difficult as defending it to your upper-middle-class and out-of-town friends. Understanding that there is much more complexity to poverty (and lack of education and drug crises) than laziness and lack of ingenuity means that while I try to save the anger from those that marginalize, I must also save the anger from those that perpetuate the stereotype. And to do it, I must pretend like it doesn't affect me and my own successes because I am, "too smart," to allow myself to make those same excuses.

Last week, I was twelve hours away from overdrawing my bank account. I paid a utility bill too quickly instead of waiting to get paid again and in that moment I panicked because what was I going to do about it? Then I remembered a savings account. It doesn't have a lot in it, but enough to cover a winter-sized electricity bill without being completely empty. It may have taken a bit of shuffling but what would put many under water for a week didn't cause complete pandemonium. When I sat back and thought about the shuffle I cried about it. I cried because although I work diligently to make sure that I can cover for my own miscalculations - that the first place that my mind goes is to the fear and anger of this being my life. That the safety never occurs to me first. That is the poverty of being the daughter of Appalachia. I should say, this is my own personal poverty based upon what I saw and see in the world that I live in, I guess. How can I convey this to my friends and coworkers that see a map full of blue dots of poverty as a problem of personal weakness rather than a starting point for real compassionate dialogue about what it means to have less?

When I get like this - it manifests itself into understanding the reasons why I may feel chronically without. The money that I've spent to get an education that I didn't realize I was spending. That the value proposition of student loans made so much more sense when I was eighteen and thought that I would make enough to pay them back in five years while still being able to have a decent life. The money that I spent to be married and the money that I spent to be unmarried (and the money that I spent in crisis between those two points). These things have turned into confrontations have lead to meager payoffs - including one just this past December (the weekend of my birthday, no less). As if there is a dollar amount on closure or a magical payment that would lead to unending forgiveness for acts that lead to a lifetime of emotional debt. That is poverty too, though, isn't it? The idea that throwing money or credit at a problem would end the wrongness or replace people living a better life and being better to each other or better to themselves. When I bring these things up outside of the confines of therapy I seem whiny or unrealistic. That everyone feels the way that I do and understands the implications of generational poverty. They don't and I don't to the extent of those that have less than I.

"It has always been this way, Jessica. You must understand that. Why are you making it such a big deal?"

With more than one member of my family, I have spoken about how the behaviors that we dealt with in our youth will end with us because we have the opportunities and the knowledge to do better with what we have - but will they? Will we rise above the mountains? Will there ever be a point where when I miscalculate that I don't instantly lash out at the notion that no matter how hard I work or use the tools that I have that I will be without? Will all of "our generation," of impoverished hillbillies with money and credit stop partaking in risky behaviors because we start to really feel safe at our core? Will we all stop self-soothing with short-term solutions to long-term heartaches? I can't imagine that life.

Last month I went to career counseling and after a rocky start full of administrative cock-ups and disappointing scheduling snafus the counselor turns to me, looks over her glasses and says, "Well, what do you like to do?" I turned to her with all of the politeness I could muster in that moment. I gathered every good habit that I had taught myself in the years that I had become my own champion and I said very calmly, "I'm not sure who comes to do you for career counseling, but if I had the luxury to do what I liked I wouldn't need career counseling. I do what I must in order to make my life work." That is the moment when the depths of poverty are at their grandest - not when I overdraw my bank account or when I see the balance of my 401K. It may seem like a first-world idea (and I am well aware of my privilege here - but it doesn't make the pain any less real in the moments where I cannot overcome these thoughts), but the idea that we continue in our lives putting band-aids on generational poverty is what leads to my own feelings of being bound to the mountains. I look in the mirror and think that I am not capable of living up to the conversations that I have with my family about our living being different than those of our parents. That instead of hating my job at the mill or the mine - I'll hate my job in the cubicle and count the days to retirement.

It seems so hopeless, but there is a lesson: Mountains are neutral. People are poverty.

What happens next is this: If I cannot escape the mountains...I will learn them. So, when I am free of the copious amounts of snow that keep me shoveling and shoveling, I'll hit the road and go into the mountains as far as I can go when I can. And we'll see what happens.

I've worked for the rich,

I've lived with the poor.

I've seen many a heartache,

there'll be many more.

I've lived luck and sorrow,

been to success and stone.

I've endured,

I've endured.

How long can one endure?

Comments

Post a Comment